Walking the line: A safer, more walkable Lake Charles starts here

Published 7:48 am Sunday, May 25, 2025

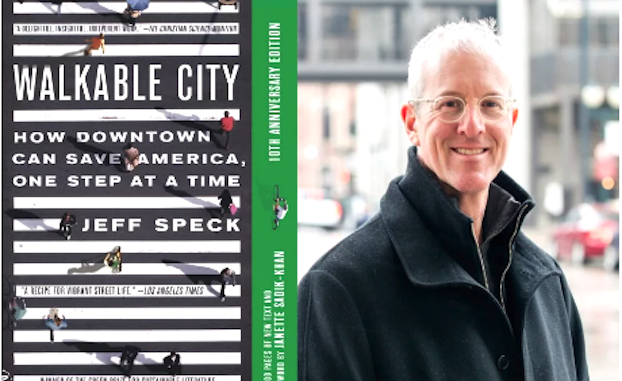

- Walkability expert Jeff Speck stopped by Lake Charles last month to tour the city and bestow his walkability wisdom. (Special to the American Press)

To begin making Lake Charles more walkable, the Community Foundation of Southwest Louisiana called in the big guns.

Walkability expert Jeff Speck stopped by Lake Charles last month to tour the city and bestow his walkability wisdom upon city officials, city planners and curious citizens alike.

Speck is an American urban designer known internationally for his books “Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time” (the century’s best-selling book on walkability) and “Walkable City Rules: 101 Steps to Making Better Places.”

With 30 years of experience, he has become a global advocate for new urbanist walkability principles. He consults cities looking to take actionable steps, some simple and some complicated, to improve walkability. After assessing the city’s current layout, he determines strengths and weaknesses in walkability and assists in drafting a more walkable design.

“If you’ve got a lot of good things going for you, I can be most helpful by making suggestions about things you can change. I really see it as my responsibility to share with cities the stuff I notice,” he said.

He was brought to Lake Charles after the Community Foundation of SWLA Board Chair Jim Rock attended the Congress for New Urbanism annual conference last year. Speck spoke there, and Rock became enraptured with his philosophy on urban development and walkability. After a chance meeting, the two connected and coordinated Speck’s trip.

While not a full consultation, he toured the city and presented his findings at the Lake Charles Event Center.

The Philosophy

Walkability is a “window into good planning.” Most of the benefits of greater walkability are clear. Walking benefits public health by encouraging pedestrians to exercise and getting them outside.

But Speck is more interested in the bigger picture.

“Walkable City,” which came out in 2012, lays out these benefits to discuss why cities need to be more walkable and how to do it.

“While people think of me in the framework of walking for health and all the different aspects of the walkable lifestyle … I’m not so interested in that as I am in what makes cities great,” he explained.“I just happened to learn through the years that if you design around walkability, you do make cities great.”

Enhanced walkability helps the environment by limiting motorist emissions, boosts the economy by supporting neighborhood businesses, and supports a strong, tight-knit community, to name just a few.

He believes it is not only a good framework for design, but it is also a concept that is digestible for the general public. “Walkability” is just the “best practices in urban design,” but walkability is an accessible idea that allows pedestrians to advocate for themselves, he said.

The “general theory of walkability” poses the question, “How do cities encourage people to walk in a society where driving is heavily subsidized?”

“Once you own a car, the smart thing to do is to use it all the time. Every mile you drive costs less than the mile before,” he said. “The smart thing to do is drive. The car is there in the driveway between you and everything, and it’s just natural to fall into the car.”

The solution is simple at first glance. To get people to walk, the walk has to be better than the drive. Speck’s walkability foundation is built on four components of a great walk: useful, safe, comfortable and interesting.

The concept of a “useful walk” has become less common. Speck said there are two ways to design a town: the traditional neighborhood or the suburban sprawl. The traditional neighborhood is compact, diverse and walkable, with most of an individual’s need within five minutes from their home.

City planners strayed away from traditional neighborhoods in the 19th century with the invention of Euclidean zoning, or single-use zoning, which was created to keep residential areas away from industrial activity. Now, it’s the most prevalent type of city planning in the United States.

But by dividing large plots of land into areas that just have one use, Euclidean zoning limits a walk’s ability to be useful. The traditional neighborhood places essential services like housing, grocery, gym, park, dining, entertainment (and coffee) all within a five-minute walk.

These neighborhoods also mitigate traffic congestion by not only keeping cars off the road, but by allowing traffic to easily flow through several connecting streets.

By contrast, the suburban sprawl hinders a resident’s ability to easily walk to resources and burdens multi-lane roads with more traffic.

The suburban sprawl is also less safe. The United States has a “traffic violence epidemic,” he said. In the last 15 years, there has been a 78 percent increase in the likelihood of being killed as a pedestrian. Pedestrians are 290 percent more likely to be killed by a car in a suburban sprawl, he said.

“So the idea that everyone wants their kid to grow up on a cul-de-sac, but once you leave the cul-de-sac, you’re exposed to this extremely dangerous environment.”

Pedestrian deaths are more likely in cities with little to no pedestrian accommodations and roads with multiple wide lanes, which directly correlates to the speed of traffic. Street designs with wider lanes, fewer intersections, one-way travel, big shoulders, and no trees create more freedom for drivers to speed.

By eliminating “elbow room” and “forgiveness” for motorists, they are forced to slow down. As an example, Speck said studies show that motorists tend to drive seven miles per hour slower when the center line is removed from a street.

“It’s contrary to common sense, but if you think about it, it makes sense,” Speck explained. “That double yellow stripe makes you feel safe as a driver and makes you go seven miles an hour faster. That’s the psychology we need to understand when we’re designing downtown streets.”

Most two-lane streets without turnlanes can handle average traffic, he added.

Safety is the easiest tenet for cities to address because they own the streets. The best way to curb speeding is to design roads with narrower lanes. This is a change that doesn’t have to be expensive.

“Don’t rebuild. Restripe. You can restripe downtown for the price of rebuilding just a few streets, and we like to see that money go as far as possible.”

The standard width for lanes is 10 feet, with an accompanying seven- to eight-foot parking lane. Parallel parking is paramount because it is an “essential barrier of steel that protects the curb from moving vehicles.”

Pedestrian safety can also be boosted by street medians with trees, wider sidewalks, and bike lanes that run between the sidewalk and lane parking.

A comfortable walk can be achieved by aligning with design principles walkers feel secure. This can be done by creating a sense of enclosure with buildings and planting that line the sidewalks. And a walk becomes interesting with trees, vibrant architecture and street art that makes a walk unique.

Walkability in Lake Charles

In its current state, the region “urban design adjacent,” Speck said.

Downtown Lake Charles is well-situated to become more walkable, but the city’s current infrastructure raises safety concerns for pedestrians. But he believes the new urbanist ways of thinking about pedestrian safety could greatly benefit Lake Charles because the city’s street design process is “broken.”

“I’ve heard that kids are walking to school on the four-foot sidewalk with the rollover curbs adjacent to 13 lanes on Nelson Road, and that shouldn’t be happening.

“I’m sure the engineers working in your city want it to be safe. But this idea that safety comes not from forgiveness, but from actual constraint, is one that hasn’t taken hold here yet,” he said later while acknowledging recently-striped 15-foot lanes.

Pedestrian safety in Lake Charles can be improved by restriping roads, especially the downtown streets, to shrink lanes and add street parking. Kirby and Ryan streets could be reduced down to two lanes, he noted.

To make walking more comfortable downtown, the street edges need to be developed. He highlighted the Lake Charles Event Center parking lot that faces Lake Shore Drive. The areas closest to the road could be developed into a safe sidewalk with street parking and trees.

Speck also suggested a focus on foliage.

“Trees are vastly undervalued, and all I can say is, it’s worth every dollar you spend on them. Palm trees, however, are not really trees,” he joked. “You should stop using palm trees.”