By Jeff Duncan

Special to the American Press

EDITOR’S NOTE: Last in a series of stories about the eight inductees to be enshrined in the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame Saturday in Natchitoches.

Inscribed vertically along the back of Marques Colston’s biceps are the words “Quiet” and “Storm,” an ode to the nickname he was given by a childhood friend.

Few nicknames have ever been more apt.

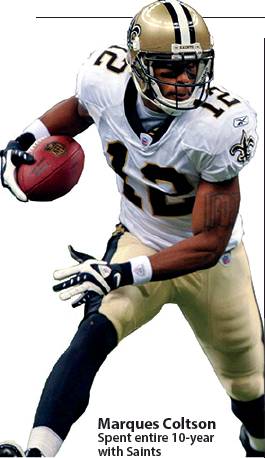

During his stellar 10-year playing career with the New Orleans Saints, Colston was a steady, stealthy force who let his play do his talking for him — on and off the field. In a league known for loquacious, attention-craving wide receivers, Colston was different.

He didn’t pout if the offense didn’t run through him. He didn’t demand the ball from his quarterback. And when he scored a touchdown, he didn’t dance or mug for the cameras. He simply tossed the ball to the official.

“That just wasn’t me,” said Colston, who adopted the expression, “Two ears, one mouth” as a personal credo. “I don’t like attention.”

But attention was impossible to avoid with that kind of talent. In 10 seasons with the Saints, Colston set club records for career receptions

(711), yards (9,759) and touchdowns (72). His 28 100-yard receiving games are tied for first in club history. All 72 of his touchdowns came on passes from Drew Brees, making the duo the sixthmost prolific combination in scoring pass plays in NFL history.

Now for Colston, even more attention. He is being inducted in the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame Saturday in Natchitoches, as the 17th player who spent all or most of his career with the Saints to be recognized — the first from the Super Bowl winning team.

There was no question about Brees’ ability to perform. But soon, the word was out on Colston.

“He had excellent hands,” Saints head coach Sean Payton said. “The consistency. The professionalism. You knew exactly what you were going to get from him, every day, week in and week out.”

Colston’s work ethic and humble personality were forged from blue-collar roots.

He grew up a couple of miles from Susquehanna Township High School in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, a town of about 50,000 people near the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

His mother assisted patients on the overnight shift at a local nursing home. His father, James Rush Colston Jr., an Army veteran, was an investigator for the Harrisburg Department of Community Affairs.

James Colston Jr., a massive man, died of a heart attack when Marques was 14. But he set an enduring example as a young league coach and mentor. A former Canadian Football League player, at 6-foot-5, 350 pounds, James Colston towered over the kids he coached in youth leagues. He served as a mentor to hundreds of troubled youth in the Harrisburg area as a little league coach and foster parent. The Colston house was a hub of activity in the neighborhood, where kids would gather to play pickup basketball on or swim in the above-ground pool.

“Sports was always my social outlet,” Colston said. “I never really went out. I never was one to party or anything like that. Sports were my release socially. I had foster brothers and sisters my whole life.”

Marques never filled out to his father’s dimensions. In fact, his lean, gangly build kept major colleges away. It didn’t help that he played in Coach Larry Nawa’s runbased offense at Susquehanna Township, either.

Nawa, sent highlight tapes to 150 colleges, but Colston received one scholarship offer from a Division I-A school: Missouri. And that came after he’d already committed to play at Hofstra.

Hofstra was a few hours away on Long Island, New York, and featured an attractive passing attack that produced NFL wide receivers Wayne Chrebet and Charlie Adams.

Colston made an immediate impact and eventually blossomed into a 220-pound NFL prospect before a shoulder injury during his junior year sidelined him. He came back to star as a senior, catching 70 passes for 975 yards, finishing as the school’s second all-time leading receiver.

Still, there were concerns. Because of his 6-4, 220-pound frame and pedestrian 4.54 speed, some NFL teams worried that he might not have the speed. Others thought he might be best suited to switch to tight end. This “tweener” status led most teams to discount him.

The Saints selected Colston with a compensatory pick in the seventh, the 252nd player in a 255-man 2006 NFL draft. The Saints’ seven-man draft class — their first under Payton — was headlined by Heisman Trophy winning running back Reggie Bush and included future franchise cornerstones Roman Harper, Jahri Evans, Rob Ninkovich and Zach Strief.

Colston’s modest credentials ensured that he arrived with low expectations. His first Saints minicamp was so bad, he secretly wondered if he would make the team. He labored in the Louisiana humidity and his back locked up.

A conversation with his wide receivers coach at Hofstra helped. Jaime Elizondo told Colston “I don’t think you know how good you are.”

Colston trained diligently over the summer and was in the best shape of his life. Saints players began to notice the wiry rookie with the sure hands. Colston, it seemed, caught everything in sight and quickly earned the confidence of quarterback Drew Brees.

“Drew made me feel comfortable from Day One,” Colston said. “To have a quarterback like that take you under his wing and want to help you produce is definitely a confidence boost.”

Veteran receiver Dontè Stallworth compared Colston to a young Terrell Owens because of his size and athletic ability and instructed him to watch game film of Owens to learn how to use his skills.

“He was very humble and wanting to learn because of the situation with him being the thirdto-last pick in the draft,” Stallworth said. “He struggled a little bit at first, but then at training camp, I just saw that guy blowing up.”

A few days later, the Saints traded Stallworth to the Philadelphia Eagles, validating their confidence in Colston, who would go on to catch 70 passes for 1,038 yards and a team-high eight touchdowns in his breakout rookie season.

“I had confidence I was going to be a good player in this league, but my rookie year, no, I can’t even lie to you: I walked into a great situation,” Colston said. “Playing with a quarterback like Drew and a coach like Sean Payton was a huge reason for my success.”

With his precise routes and sure hands, Colston developed into the go-to receiver in the Saints prolific offense. He started 106 games and missed 10 total because of injury in his 10 seasons. He led the Saints with seven catches for 83 yards in their 31-17 win over the Indianapolis Colts in Super Bowl XLIV.

“As a seventh-round pick you’ve got maybe a 3 or 4 percent chance of becoming a starter at some point in your career, and even when you do make the team, your staying power is 31/2 years,” Colston said. “For me to be a Day One starter and stay 10 years and win a Super Bowl on top of that, none of that was supposed to happen.”

Since his playing days ended, Colston has become a successful entrepreneur and businessman. He is a part-owner of the Arena Football League’s Philadelphia Soul and has invested in several other start-up companies across the nation.

Colston’s off-field success didn’t happen by accident, Nawa said.

“Marques was a coach’s dream,” Nawa said. “He was extremely talented, but he never let it affect him. He was a team player, a quiet, yes-sir, no-sir type of kid. He worked hard at everything, even though he was doing more blocking than catching passes at that time. He was a leader. He worked for everything that he got.”